About this deal

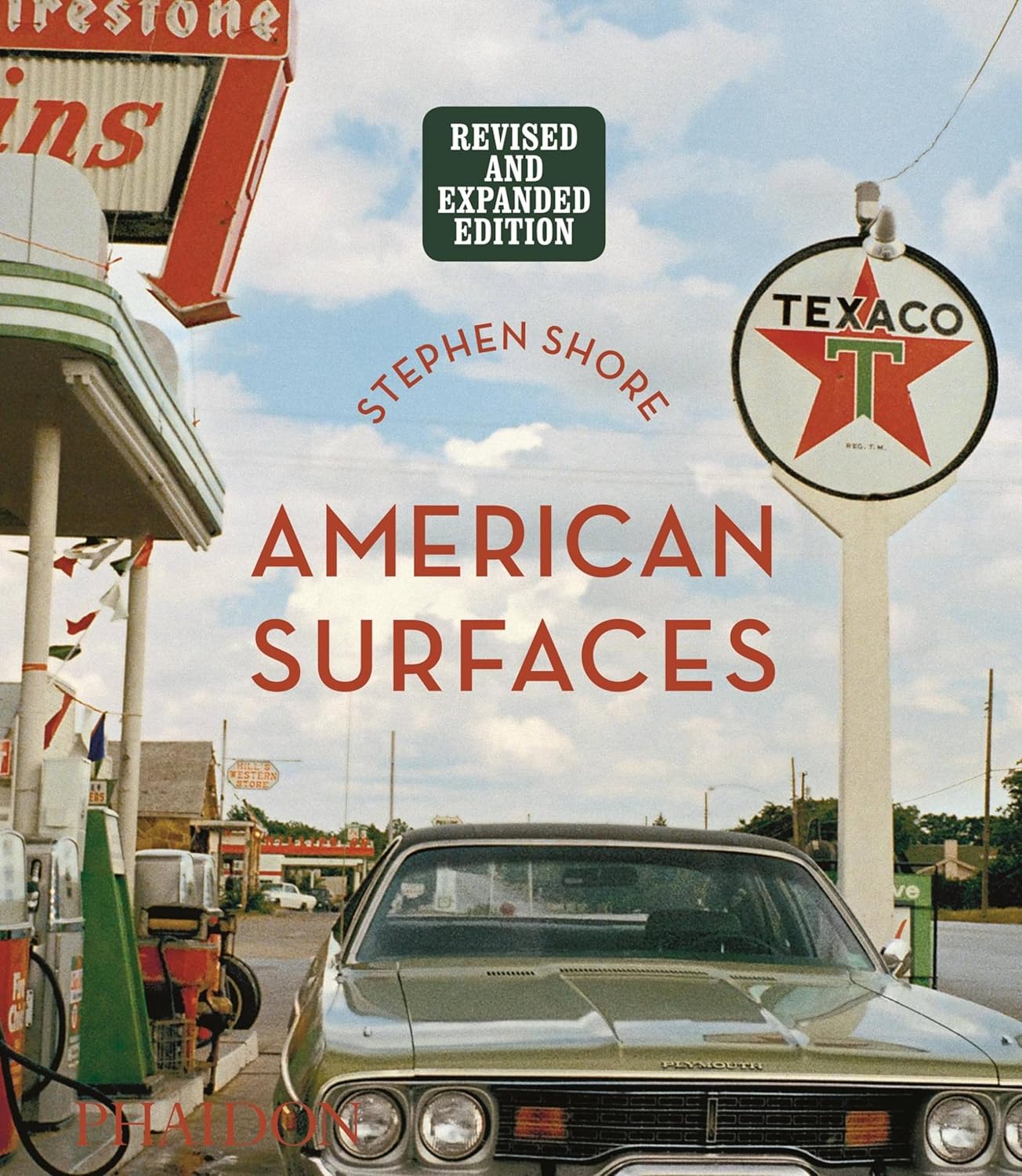

This photograph of an intersection in Oklahoma is among the image sequence known as American Surfaces, taken on Shore's first drive across the United States. At the centre of the image is the point where two roads intersect, marked by a set of traffic lights and a vertical sign marking the Texaco station visible behind two cars on the right side of the image. The image has been taken late in the day and the lights are bright against the faded blue and orange sky, the dark green of the nature strips and the grey of the road and the foreground parking lot in which crumpled newspapers lie discarded. American Surfaces is intended to be seen as a sequence, in which the minor details of life on the road, including food on tables, beds and televisions in motels and gas stations such as this, build to communicate a sense of the North American interior as an anonymous monotony. Reflected in the title of the work, the details recorded in American Surfaces are superficial, yet together they build a bold and insightful portrait of the social and geographical landscape specific to North America at that time. Prior to making American Surfaces, Shore’s work had focused almost singularly on New York, where he grew up. This project marked a formative point in his career when the concept of the road trip became – as it remains – integral to his practice: immediately after finishing this project he began his seminal series Uncommon Places (published 1982). Working in a photographic tradition established by American photographers such as Robert Frank (born 1924) and Walker Evans (1903–1975), in American Surfaces Shore established a new method of recording vernacular scenes of life in North America. The artist has stated that he set out to record ‘everything and everyone’ he came across (Stephen Shore, artist talk, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco, 23 February 2012, http://www.americansuburbx.com/2012/01/asx-tv-stephen-shore-sf-moma-artist-talk-2012.html, accessed 21 November 2014). His approach – loosely diaristic and serial in nature – together with his non-hierarchical framing of the image and grid-like method of presentation, indicated links with minimalist and conceptual practices of the 1960s and 1970s. All great American photographs have one thing in common: power lines. This is not, strictly speaking, true. But it often feels true, especially when you look at street photography. Electricity tends to follow our roadways, just like documentary photographers. So power lines inevitably appear in their pictures. And the way an individual photographer confronts them can illuminate his style of seeing. You can observe Walker Evans’s mastery with the camera, for instance, in his treatment of power lines. He admitted them into photographs not, like most of us, by unhappy necessity, but with formal artistic intention.No one was better at it than he was—except for maybe Stephen Shore. I see much of your work, especially the digital work, as a sequence of enjoyments. You like the world. But, beneath that, there’s a serious sort of drive, which I don’t understand but am trying to. Your easygoing attitude doesn’t fool me, unless I’m a fool not to honor it.

Shore took this photograph, along with others during his first year working on Uncommon Places, with a 4 x 5 Crown Graphic camera, wishing for greater accuracy with framing and a higher quality image than had been possible with his Rollei, despite the challenges this posed in taking the photographs he desired. This image required Shore to stand on a chair and raise the camera, attached to a tripod, above him on an angle. The apparent simplicity of the image, which erases Shore's authorial presence and the difficulty with which the camera was balanced, is belied by the shapes, lines and framing, all of which reveal the photograph as deeply considered. The diagonal lines of the placemats at the top and right hand side direct the audience's eye into the image, the framing of the pancakes by the plate and placemat marks this area of the image as particularly significant and the interplay of small and large circular items serves to hold the audience's attention and stimulate sustained consideration. Stephen Shore was born in 1947 and grew up on New York City's Upper East Side. Shore's family was Jewish, and he was the only child. The family owned a succesful business and Stephen lived a privileged existence, with annual trips to Europe and regular exposure to art and other forms of culture. He was given a darkroom set by an uncle when he was six, which he used to develop his family's snapshots, taken with a simple and inexpensive Kodak Brownie, often experimenting with different ways of printing the images using cardboard masks. Shore had little practice taking his own photographs, however, until the age of nine, when his parents bought him a 35 mm camera. SS: Well, I grew up as you said in New York City and most of the traveling I did was to Europe. But then, in 1969, I went to Texas with some friends of mine who were from Amarillo, and I started going there more in the summers and was introduced to part of the country that I hadn’t experienced before. We sometimes used Amarillo as a base for other trips and I wanted to explore that. So, it was unfamiliar to me and I felt very much like an explorer venturing out into a country I didn’t know.

Out of Print

As a teenager, Stephen Shore was interested in film alongside still photography, and in his final year of high school one of his short films, entitled Elevator, was shown at Jonas Mekas' Film-Makers' Cinematheque. There, Shore was introduced to Andy Warhol and took this as an opportunity to ask if he could take photographs at Warhol's studio, the Factory, on 42nd Street. Warhol's answer was vague and Shore was surprised to receive a call a month later, inviting him to photograph filming at a restaurant called L'Aventura. Shore took up this offer and, soon afterward, began to spend a substantial amount of time at the Factory, photographing Warhol and the many others who spent time there. He had, by this point, become disengaged with his high school classes and dropped out of Columbia Grammar in his senior year, allowing him to spend more time at the Factory. Today, Shore is the director of photography at Bard College, where he started as a professor in 1982. He wears tortoiseshell glasses and a wardrobe of corduroy, wool, and tweed. His hair is gray and slightly wild. He appears so adapted to the professorial role that it’s a surprise to learn that he has almost no formal schooling of his own. From here, it’s going to feel like I’m skipping forward for a moment. The American Surfaces series was shot between 1972 and 1973, but it wasn’t published as a proper book until 1999 – nearly three decades later! Before this, it existed merely as a gallery exhibition. Shore was just 24 years old at the time he took these images, yet served another full lifetime in this respect when the book was eventually published at age 51. At the time that this series became a book, his life – and his career for that matter – were very different.

Together, they amounted to a new topography of the vernacular American landscape, his style in places approximating what came to be known as the snapshot aesthetic, in other places adhering to a detached, almost neutral formalism that only added to the deadpan everydayness of his images. Shore later described his democratic approach thus: “To see something ordinary, something you’d see every day, and recognise it as a photographic possibility – that’s what I’m interested in.” Though dismissed at the time by many critics, his style has been enduringly influential and he is now recognised as one of the greatest living photographers. When you left the Factory, you began shooting in color, which at the time was widely regarded as a kitschy, banal mode. What prompted that switch? Content inseparable from attention to form. It occurs to me that there’s no such thing as a definitive Steven Shore photograph, except that it’s by default like nothing else. I recognize it, but not as an instance of “style.” It’s more like entry to a zone of immediate experience. I feel a little lost, as I do in my real life. You don’t pin down; you unpin up, if that makes any sense. VH: Absolutely! Thank you so much for speaking with me and with Phillips. We’re really excited about the new edition of 'American Surfaces.'But this is only part of the story. The question remains: why this particular intersection, on this day, in this light, at this moment? That’s more like what you’ve called instinctive. There’s the sense of something taking over. I found on my road trips that, after a couple of days of driving and paying attention to what I was seeing, I would get into a very clear, quiet state of mind. By geographically and chronologically charting the photographer’s original footsteps, the book becomes a supra-documentary, re-centering its focus with each new form of the work, making the larger undertaking its own best subject. Shore has referred to both this and the expanded re-issue of another of his books as the equivalent of “director’s cuts”, but that single metaphor shortchanges the larger implications at hand. To begin with, this reincarnation of American Surfaces as a kind of meta-work might be read as positioning the book questionably within an educational or service function, rather than as a sui generis aesthetic form. Considering at least part of its origin within a conceptual milieu, this becomes doubly problematic. What such a book might benefit from as a historically corrective omnibus version becomes its liability as a less potent incarnation of original art. This is not a fault of this edition specifically however, so much as the larger trend towards photography book re-issues, as one might consider the case to be with the latest edition of Walker Evans’ Many Are Called, among others. There are plenty of opportunities these days to see them for yourself. MoMA has devoted half of a gallery in its “XL: 19 New Acquisitions in Photography” exhibit to Shore’s career; in November, the Sprüth Magers gallery in London will also host a curated retrospective; and in early 2014, the Rose Gallery in Los Angeles will show a selection of Shore’s work. The change was not a deliberate stylistic overhaul but a natural response to the technical differences of the large-format camera. 8x10 color is, Shore said, “the most cumbersome and expensive photographic process possible.” As a result, he had to be much more mindful of when and why he took a picture. Influential upon future generations yet symptomatic of its own time, the material is likewise deeply referential to its forebears: its eclectic span is a rebus in the Rauschenberg sense, and a roadmap, both literally and metaphorically. There are frequent nods to Eugene Atget and Walker Evans, as well as Warhol and Ed Ruscha, but Shore’s contemporaries are also included. The presence of Bernd and Hilla Becher is felt throughout, and in a wry mode of disclosure, Shore concludes the new book version of the series with a portrait of William Eggleston that makes plain the wider allegiance to that photographer that arises in so many other images. To see the whole however is to know that it is definitively a work by Stephen Shore, imbued as it is with his particular sensitivity. As a spectacularization of the banal, it reads like Pop, but is too clearly warm-blooded to be limited by that label.

Related:

Great Deal

Great Deal